Connecting with Compassion

Before her three tours at Fort Meade, former Chief of Preventive Medicine Services Col. Beverly Maliner (Ret.) was given countless opportunities to develop her expertise of diagnosis and clinical regimens. Each experience fueled her drive to broaden her worldview while also humbling her with a repeated observation — the need for human compassion.

Beverly grew up in a household that valued learning, interdisciplinary thinking and serving the community. She was able to combine her natural ability to mobilize a consensus with her interest in medicine when she attended medical school to study osteopathy.

Beverly’s career led her to opportunities in urban and rural areas nationally and internationally caring for the general public, U.S. service members, civilians and contractors, as well as immigrants and nationals all over the world. She has cared for clients suffering from drug addiction, AIDS, abuse and mental illness; treated patients in hospitals, clinics, combat zones and in family practice; she has conducted healthcare counseling, chemical warfare training, quality assessments and public policy reviews. While Beverly is highly educated and has earned a unique skillset, it’s the lessons she’s learned from her clients that influences her the most.

“I have worked with people who came from all kinds of countries and cultures,” Beverly shares. “I have worked with people who lived in all kinds of different socio-economic levels…and I met tremendous courage and I met tremendous forthrightness.”

Beverly’s remarkable background, which also includes public health and community development, gives her a very solid foundation for decision making, advocacy and ongoing discussions about inclusive healthcare. As a branch of medicine that is often overlooked, Beverly turned her attention to occupational medicine in 1997.

“Army Family Medicine is occupational medicine,” Beverly explains. “It’s about keeping soldiers and their families prepared to do what they need to do in their lives. Today, to do what you can to ensure they’re ready in the future, as well. It’s not about rescue. Rescue may be part of it, but there’s a driving philosophy beyond that which says, ‘You need to be able to get up in the morning and you need to be able to do these things.’ So the mindset, as it turns out, is exactly the mindset of occupational medicine. It’s to focus on the workforce.”

Beverly arrived at Fort Meade in 2010 to begin building a public health team. Her role included becoming a member of the Community Health Promotion Council (CHPC), a garrison-wide group created to bolster the health and welfare of the Fort Meade community. Through their research, the CHPC realized there was a need to rethink some of its language so that the Fort Meade community is fully represented.

“We needed to redefine our definition of warrior,” Beverly explains. “It needed to be of terminology that is maximally inclusive and to fully include the government civilian worker.”

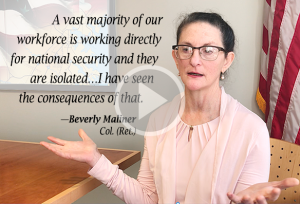

Beverly and her team were seeing massive distress in the civilian workforce, sometimes to the point of total despondence. As technology in cybersecurity advances and military missions are executed from Fort Meade workstations, civilians, contractors and DoD personnel are faced with how to cope with challenges once reserved for the service member in combat. However, the typical camaraderie of a deployed environment is missing, as is the ability to share their security clearance burdens with friends and family. Add our fast-paced culture of commuting, raising families and career advancement, Fort Meade personnel are often isolated. New approaches to building camaraderie and connection for our workforce are now necessary, as is the need to support the toll taken on their families.

“Military life is a busy, high-intensity environment where the focus is always external,” Beverly shares. “We need to learn how to breathe and to go internal, so we can better cope with our daily demands and recover.”

Unsurprisingly, when discussions about the anticipated Education and Resiliency Center began in 2011, Beverly’s role was highly valued and well respected. Not long after the definition of warrior was clarified, the definition of resiliency was also assured.

Fort Meade characterizes resiliency as a combination of two factors: a sense of belongingness and a confidence that the necessary support and resources are accessible. Like many, Beverly envisions the Education and Resiliency Center as not just a centralized location for programs, lectures and appointments, but also a place where work relationships can continue and, hopefully, help offset the inevitable sense of isolation for those committed to the safety of our nation. As someone who has seen first-hand the consequences of those not having a sense of belongingness nor confidence in accessing much needed support and resources, Beverly is also aware of the ripple effect these consequences have on national security.

“If they don’t get the help they need, then they lose their livelihoods—and we lose all that workforce knowledge, all those skills,” Beverly says. “We just lose it; we’ve invested so much, and they’ve invested so much, and we lose it. So, what if they have a healthy place to go?”

Help foster a lifestyle of practicing preventive self-care for our nation’s workforce and their families by donating today to the Education and Resiliency Center at Fort Meade. Join the FMA Foundation as we support those on the frontlines in our own backyard.