June 18, 2020 – From a global pandemic to a housing shortage to surprisingly high bids for construction, Fort George G. Meade has been wrestling with a range of operating challenges. At the Fort Meade Alliance Annual Meeting on June 18, however, garrison leadership described how they are meeting those challenges and strengthening Fort Meade’s future.

“When there is chaos, you can find opportunity,” said Garrison Commander Col. Erich C. Spragg, Garrison Commander. “In many ways, I think Fort Meade has led the way in getting through these crises.”

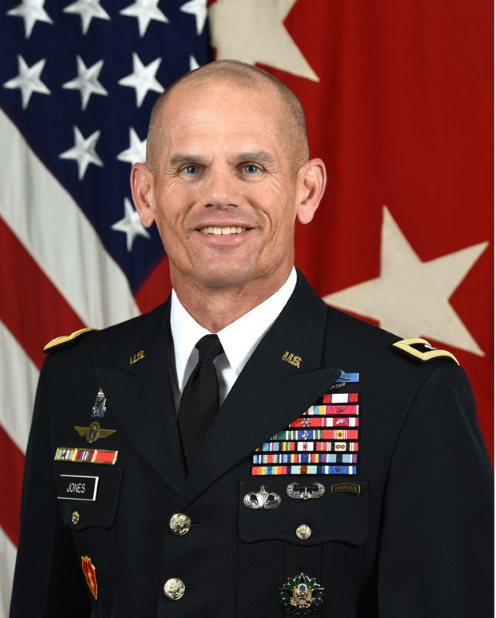

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Maryland, Fort Meade closed down many services very quickly to protect military personnel, family members, civilian workers and individuals receiving services on post, and also to assure the continuation of critical missions, said Major General Omar J. Jones IV, Commanding General at the Joint Force Headquarters, National Capital Region.

Those same priorities “will probably cause us to be a little bit slower [reopening] than what is happening off the installation because we can’t take risk with critical missions,” Jones said.

Some services will resume in the next three to four weeks, albeit under new protocols.

“Childcare is my number one objective to get open as quickly as possible, but safely,” Spragg said.

CDC and DoD guidelines about how to function safely in the midst of an ongoing COVID-19 outbreak will drastically reduce Fort Meade’s childcare capacity.

“The ballpark figure is a 60-percent reduction… Before COVID, about 1,100 children were enrolled in our CYS programs. Once we start opening…that capacity is only going to be about 432,” Spragg said. “There are going to be a lot of people looking out into the community for that childcare support and they are going to run into the same problems out there, so that is a huge concern… But we’ll get though it. We always do. And we’ll come out better on the other end.”

Spragg pointed to a different kind of shortage as the other crisis he has contended with since he assumed command of the garrison 22 months ago. Fort Meade has a barracks deficit of 1,800 beds. That shortfall means “there is no place for junior enlisted soldiers to live on the installation,” he said.

Consequently, the Army has to provide those service men and women with housing stipends and send them out to find their own accommodations in the community.

“There are a whole bunch of drawbacks with that,” Spragg said. “First and foremost, this is your most vulnerable population” who are unaccustomed to managing monthly bills and other demands of living independently.

The Department of Defense is planning two construction projects in 2024 and 2025 which will create 1,100 new beds.

Meanwhile, the garrison is also dealing with another looming bed shortage. Four barracks complexes, serving sailors and airmen, currently occupy land that the National Security Agency and U.S. Cyber Command require in order to complete their expansion on Fort Meade. Consequently, the Army and the NSA are currently negotiating a jointly funded project to build replacements for those barracks in Fiscal Year 2022.

Supporting 119 commands and agencies and a population of 57,000 people, Fort Meade is also dealing with other infrastructure needs. Construction of the new Rockenbach gate has dragged on since 2012. The new entrance is scheduled to open in the fall and is expected to reduce congestion on Maryland 175. Meanwhile, plans to build a new entrance on Reece Road have hit a financial hurdle. Although the federal government approved $19.6 million for the project, all construction bids came in $10 million over that budget. A request for additional funds is currently before a Congressional subcommittee and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has expressed optimism that the project will be able to proceed later this year, Spragg said.

Leadership is also striving to make Fort Meade “the installation of choice” for service members and civilian employees. One key to making it attractive to military families is great schools that are connected to the military and can support military children.

“My hope is that when future military members are assigned to Fort Meade, what they will be looking for is how can I find a house on the installation…because I want my kids to go to the feeder schools and Fort Meade High School,” Jones said. “That doesn’t get said a whole lot right now. I think we can do it, but we’ve got an uphill climb.”

One potential improvement at Meade High would be to combine the expanded cyber curriculum and cyber range with classes in Category 4 or 5 languages, such as Arabic, Chinese, Pashto, Farci, Russian or Korean, Spragg said. That combination would give graduates clear advantages in college and job competitions “and by the way, the mecca of all things foreign language and intelligence is right here at Fort Meade. This is how we would keep people here and retain and attract talent.”

After years of effort, Fort Meade is on the verge of one major improvement in services to its community, namely the redevelopment of Kuhn Hall into an Education and Resiliency Center.

“Due to the nature of work we do on this installation with a lot of classified stuff…a healthy decompression after work is kind of hard to do,” Spragg said.

That strain may be a contributor to above-average rates of domestic violence, child abuse and alcoholism on post, he said. The Education and Resiliency Center could provide vital and highly impactful services to individuals involved in missions critical to national security.

The Kuhn Hall renovation is a joint project between Fort Meade, the Fort Meade Alliance and the Fort Meade Alliance Foundation.

“Thank you to the entire alliance for what you have done,” Jones said. “Over the decades, since 2003, your support to the Fort Meade community … [has been] helping us take care of our people, helping us communicate what we do and helping us advocate for what our people need. You all just do a tremendous job with that.”

Reflecting on another challenge that is currently confronting not just Fort Meade but the entire country, Jones said it’s important for people to join in the current “deeply meaningful discussions about race… [so that] we can live the words of our declaration, live the words of our Constitution and really make them part of who we are.”

“When folks outside the military look at us, we look very monolithic,” Jones said. “We dress the same, we use some of the same language, we have a lot of the same culture and customs. But the really good organizations, both in the military and outside, are ones that not only acknowledge the diversity of teammates but embrace it and celebrate it.”

To create truly effective, high-performing teams and to foster deep loyalty to organizations and missions, military leaders “really have to know your people,” Jones said. “We have to listen a lot more than we talk. You can’t ever truly walk in someone else’s shoes, but you can listen to them, you can be empathetic to them and you can appreciate their personal circumstances. You can appreciate the path that they have walked, you can appreciate their background.”